|

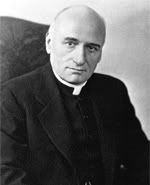

Saving Monsignor Ryan

Ryan's story and treatises help us reveal that these nefarious characters have hijacked Catholic theology in order to pursue a very non-religious economic agenda based upon an "I've got mine and the hell with you" attitude. Monsignor Ryan is the very tonic to help cure the plague of Catholic Right revisionist history. Born of Irish immigrants in 1869 Minnesota, John A. Ryan was a champion of civil liberties and economic justice. Ordained a Catholic priest in 1898 he blended late Nineteenth Century Midwestern Progressive Populism with a burning sense of Neo-Thomist ethics. He wed theology to economics and 1906 published his first major economic work, A Living Wage, a treatise that defended the ownership of private property, but simultaneously "spurned overly acquisitive and unregulated free market capitalism as economically unhealthy and morally bankrupt."(i) In 1915 Ryan attained a professorship at Catholic University where he taught until his retirement in 1939. To the chagrin of today's Catholic Right, he was both an early board member of the ACLU as well being a close friend of the organization's founder, Roger Baldwin. Yes, the ACLU. Not exactly the neocons' idea of fighting "moral relativism," eh? In 1916 he published the first of several editions of his Magnum opus, Distributive Justice: The Right and Wrong of Our Present Distribution of Wealth. Drawing upon Aristotelian notions of natural law ethics, he outlined a very contemporary liberal concept of the just distribution of profit in relation to contribution, merit and special talents. With the coming of the New Deal he became a confident of FDR on economic matters, earning the moniker, "the Right Reverend New Dealer." Unlike today's neoconservative Catholics who actively seek to replace a pluralistic notion of morality with one based upon traditionalist orthodox Catholicism, Ryan demonstrated how distributive justice ethics converged with American ideals rather than supplanting them. "Theocracy is a thing of the past" Ryan wrote in 1894, "the Church must henceforth depend upon her own worth and her own intrinsic adaptability for her successes. How is she most likely to succeed? Why, by taking advantage of the permeating tonic of the age, by appreciating its aspirations, and by making these her own in so far as they are conductive to the glory of her Divine Master." Monsignor Ryan would oppose artificial birth control, abortion rights and embryonic stem cell research. But unlike the theocons, he understood that opponents on biological issues could be strong allies on economic issues. As the Notre Dame historian John T. McGreevy noted, "The civil liberties lawyer Morris Ernst, before challenging the 1935 congressional testimony of Father John A. Ryan on contraception carefully announced, '(O)n many battle fronts in the fight for freedom of the press, for labor, and so forth, I have fought side by side with Father Ryan.'"(iii) More important however than neocon selectiveness on the evolution of differing schools of natural law thought is their avoidance of distributive justice something that Catholic neocons such as Michael Novak conveniently ignore. And they do so for good reason: it exposes the hypocrisy their entire argument. Neoconservatives such as Michael Novak acknowledge that capitalism is a "for sinners" but fail to provide any remedy for the collateral effects of sinfulness resulting from human egotism. In doing so, they place too much faith in the self-correcting nature of the market. The free market, just as with any other mechanism, is imperfect and thus prone to error. But the only corrective measure they acknowledge is loss of profit. They fail to acknowledge that the property concentrated in the hands of a powerful few can be used to domineer the many. Beyond that, Novak and "Whig-minded" others of the Catholic Right offer no mechanism for extending property ownership to the population at large, save becoming virtuous by practicing orthodox Catholicism. A particularly good example of how devout religiousness does not automatically translate into virtuous business leadership is the case of Tom Monaghan, icon and financial source of Catholic Right causes. Monaghan, though born a Catholic, sought out a more traditionalist form of the faith than most other Catholics. After building his Domino's Pizza empire he sold it in 1998 to Bain Capital (an investment company co-founded by Mitt Romney) for a price in excess of one billion dollars. The former pizza king has since been investing in orthodox Catholic causes such as the Thomas More Law Center, his dream school -- Ave Maria University, and Frank Pavone's militantly anti-abortion Priests for Life. The Wall Street Journal has reported that Monaghan has thwarted attempts by university employees to unionize. When asked if he saw a contradiction in his efforts, since unionization is supported by the Catholic Church, Monaghan replied, "I think that [the church] hierarchy doesn't know as much about those things as they do about their theology.(iv) Monaghan personifies the absurdity of Novak's contention that leaders of business and industry who become virtuous through faith require no oversight from government.

Saving a Legacy This omission leads Novak to another startling conclusion: On page 247 of The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism Novak claims that third-way Catholic economics (a middle course between uncompromising varieties of Marxism and laissez-faire, anything goes capitalism) was never truly tried. However, there were several socialist-inspired concepts at heart of the New Deal (but clearly refined to save capitalism, not destroy it); they were very much the essence of Monsignor Ryan's economics. Third-way thinking, with its emphasis on contribution being reciprocal to receipt was one of the justifications for progressive taxation. And more importantly, because it was part and parcel of the New Deal its ideals were instrumental in creating the modern middle class. But perhaps Novak's greatest omission is a discussion of what leads many to socialism: laissez-faire, buccaneer-style capitalism. When "the sinners" who engage in capitalism do so without any sense of responsibility towards others, without any sense of receipt based upon corresponding contribution, using their disproportionate economic power to threaten the economic security of those less powerful, that is when socialism in its less democratic forms becomes attractive to people. What Novak doesn't seem to get (or more probably does not want to get) is what Monsignor Ryan and other social justice Catholics have long understood: to be secure from financial catastrophe is freedom. Economic equity cannot be had on a purely voluntary basis: government needs some muscle to prevent and to punish bad behavior in the pursuit of wealth. Novak, Weigel and most other neoconservatives - Catholic or otherwise - are unable or unwilling to acknowledge that 13th century scientific natural law conclusions cannot be uniformly applied to today's bioethical issues; and that similarly, Locke's and Adam Smith's ideas cannot be uniformly applied to twenty-first century realities. The same principle applies to church documents such as Summa Theologica. Perhaps Constitutional scholar Stephen Holmes put it best, "Modern liberalism is best understood as a rethinking of the principles of classical liberalism, an adaptation of these principles to a new social context where individual freedom is threatened in new ways."(v) Monsignor Ryan understood that when religious hierarchies risk corruption when they are financially tied too closely to a wealthy elite: when only those of superfluous wealth have the ability to shape policy within historic religious institutions. When any religious organization becomes a convenient tool of wealthy interests, it loses its credibility when offering social criticism. America and Catholicism don't need any more Novaks channeling libertarians such as F.A. Hayek and politically aligning with the Religious Right. Instead, it needs leaders who make the economic needs of the average worker - an equally and often far more important player in wealth creation than seven-figure CEOs and mega-stockholders - a top priority. Catholicism needs leaders like Monsignor John A. Ryan.

NOTES: The Catholic Right: A Series, by Frank L. Cocozzelli : Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four Part Five Part Six Intermezzo Part Eight Part Nine Part Ten Part Eleven Part Twelve Part Thirteen Part Fourteen Second Intermezzo Part Sixteen Part Seventeen Part Eighteen Part Eighteen Part Nineteen Part Twenty Part Twenty-one Part Twenty-two Part Twenty-three Part Twenty-four Part Twenty-five Part Twenty-six Part Twenty-seven Part Twenty-eight Part Twenty-nine Part Thirty Part Thirty-one Part Thirty-two Part Thirty-three Part Thirty-four Part Thirty-five Part Thirty-six Part Thirty-seven Part Thirty-eight Part Thirty-nine Part Forty Part Forty-one Part Forty-two Part Forty-three Part Forty-four Part Forty-five Part Forty-six Part Forty-seven Part Forty-eight Part Forty-nine Part Fifty Part Fifty-one Part Fifty-two Part Fifty-three Part Fifty-four Part Fifty-five Part Fifty-six Part Fifty-seven Part Fifty-eight Part Fifty-nine Part Sixty Part Sixty-one Part Sixty-two Part Sixty-three Part Sixty-four Part Sixty-five

Saving Monsignor Ryan | 12 comments (12 topical, 0 hidden)

Saving Monsignor Ryan | 12 comments (12 topical, 0 hidden)

|

||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

print page

print page